- Home

- Our Activities

- Past Studies/Projects

- Japan in Digital Geopolitics

Japan in Digital Geopolitics

Finished

Director / Senior Researcher, International Information Strategy Research Department,

Center for International Economic Collaboration (CFIEC)

Makoto Yokozawa

Increasingly Complex Digital Geopolitical Games

Needless to say, "geopolitics" is designed to discuss a country's policy based on the history and current state of its geographic features, politics, economy, and culture. Digital technology has dramatically advanced the development of communication technology over the last century, causing the loss of geographical distance in much of the information we come into contact with on a daily basis. It is repainting our location in the real world and rendering the strategy of long-distance communication meaningless. Meanwhile, while the traditional North-South problem and the Cold War between East and West are taking shape, a new "geopolitics" on a virtual map is being formed, using "like-minded friendly relations" as the distance scale.

In the 21st century order since the end of the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, the world economy seems to be swirling around three geopolitical centers of debate. The first is the U.S., which has reigned supreme over the world economy; the second is Europe (EU), which has overcome the fragmentation of different languages and cultures and is aiming for market unification in the region, starting with the digital economy; and the third is China, which has strengthened its national power to the limit and realized maximum production efficiency and phenomenal growth through its leapfrog strategy. Within this trilateral structure, the U.S.-China-European (U.S.-China) decoupling is central to all aspects of society, including national security, economics, human rights and environmental issues, resources and supply chains, technological development, and religion and culture, sometimes in violent conflict, and at other times in diametrically opposed, mutually influencing and sharing interests, Complicating the game situation.

Meanwhile, U.S.-European relations remain difficult to understand after the change of administrations in the U.S., and a simple recoupling (re-harmonization) is still not enough. In particular, the dominance of U.S. companies that dominate the market with cutting-edge technology and the associated economies of scale is particularly pronounced: few Japanese companies have adopted a head-on competitive strategy against GAFAM (a group of giant digital companies based in the U.S., including Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft). Meanwhile, the EU has sought to maintain the independence of the digital single market, integrating its own technology development goals and regulations, ranging from 5G and blockchain to AI. The "general" in the EU's strong regulation on privacy protection (GDPR, General Data Protection Regulation - "General Data Protection Regulation") means, first, overcoming differences among EU member states and, second, among the sectors covered by the regulation, to ensure that basic The "general" in the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDR - General Data Protection Regulation) is the manifestation of a strong idea to realize the protection of privacy as a fundamental human right within the region and throughout the world, overcoming firstly the differences among EU member states and secondly the differences among the sectors subject to regulation. In this respect, it differs from the current data protection legislation in the U.S., which is unique to each sector and each state. In addition, because the focus is on the protection of the individual data subject, lawsuits triggered by concerns between U.S. companies and European individuals often end up overturning earlier agreements between nations.

In the digital field as well, China, with its "One Belt, One Road" initiative, which aims to expand its own hegemony, is exerting such a strong influence over the entire world that it needs no further explanation here. It is no exaggeration to say that the negotiations between European, U.S., and Chinese companies over the standards for the fifth-generation (5G) telecommunications network are truly a "battle for supremacy," and for this reason there are discussions everywhere about an early shift to a more neutral "sixth generation," even though 5G is still in its infancy. However, some Japanese, U.S., and European firms still take seriously the importance of China as a huge market, production base, development base, and investment entity, and a variety of movements are taking place behind the "conflict" in a complex manner.

Digital Geopolitics and the Japanese Situation

In the context of digital geopolitics, Japan maintains deep relationships with all three poles of the US, China, and Europe. Even as China continues to decouple, its relationship with Chinese companies as business partners remains important given its geographic proximity in the real world, and it continues to rely on China for real natural resources such as rare earths. On the other hand, while Japan participates in development cooperation between the U.S. and Europe in advanced digital technologies such as AI and 5G, it is often delicately positioned within those two poles.

While expectations for digital transformation have increased in Japan over the past few years, many areas have been left behind as the effects of digital transformation have not yet reached the expected level. In Japan, there are still many situations where digitalization has been left behind and neglected. The productivity of small and medium-sized businesses and those who have been left behind in the benefits of digitalization have been forgotten, and even e-money payments and credit card payments have not progressed very well. The use of electronic certificates and electronic medical information is limited to large corporations, and the lagging digitalization of small and medium-sized operations may be dragging down the digital transformation of society as a whole.

New businesses in the true sense of the word have yet to emerge from the "utilization of data. On the contrary, systems developed by governments and large corporations for a significant percentage of the total population have been malfunctioning or failing one after another, frequently resulting in negative social impacts. The Corona disaster has amplified the voices of those who say, "If this is the case, we should never have relied on digital technology," "What was the point of going digital if this is the case," and "How many times will we be asked to input the same data?

Digitization is essentially global in nature, and the scope of its impact on existing businesses, large and small, will be much broader. Even if small businesses do not themselves use digital technology at all, the price of their merchandise and the form and volume of their distribution are greatly affected by digitalization. Conversely, it was hoped that digitalization would be seen as a bridge to global business, triggering new types of business and innovation, but this has not been the case.

Furthermore, no one has a full grasp of "what is going on" with regard to the reality of digitization. There is an overwhelming lack of evidence, enclosure of information, and a lack of understanding of the new value that comes from openly sharing information.

Circumstances surrounding DFFT (data is an imperfect resource)

Data is a new resource in the new digital economy, but its nature is very different from traditional resources in its polysemic diversity, and the meaning of ownership and management control is ambiguous.

No country completely rejects "free data distribution," and the dissonance in how it is achieved is adding to the confusion. For example, all cross-border data distribution originating and terminating in China, for example, is "China-friendly" and does not automatically generate mutual benefits from the movement, as is the case with logistics.

The discussion should bear in mind that data itself does not have universal efficacy as a resource, but rather has a difficult nature that changes its nature as a resource depending on the motives for its handling and the values of those at both ends of the distribution chain.

COVID-19's legacy of the "New Normal" and the changes it failed to fulfill.

The situation of the spread of the new coronavirus accelerated this change. Looking at the direction of this change, it can be said that simple volume (Volume) alone does not directly lead to economic value, but its freshness and quality have become the focus of attention. The meaning of agreements made under different circumstances in the past has diminished, and more up-to-date information with velocity is required to be shared quickly. Variety itself has value, and it is difficult to uniformly control the world's data with a single principle, so it will be difficult for national capitalism, human rights, or liberal capitalism to gain a decisive advantage.

In Japan, as on a global scale, this is a major shock on a national scale that occurs once every few decades, with a socioeconomic impact greater than that of the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. We have been working on digital transformation, the new normal, to at least use this impact as a catalyst for change.1)However, for better or worse, the period of time so far has not yet been enough to essentially rewrite the social and economic foundations of the society. Many documents submitted to public agencies have yet to be digitized, and electronic payment and settlement have not progressed. There is also the argument that remote work may also be harmful from the standpoint of productivity at the moment. This is partly due to the fact that the hasty and poor attempts at digital transformation have resulted in a series of system failures because the functional design, development, and operation of the system have not kept pace.

Some changes will take time, but if we simply wait for the next generation to take over, we will be repeating the same mistakes. In the recovery period that is expected in the future, leadership must be exercised so that the world will not be left behind and lapses will not accumulate.

Discussions not progressing amid lack of "data on data

Just prior to the onslaught of the new coronavirus, the Nihon Keizai Shimbun introduced statistics on cross-border data volume. China's cross-border data volume has reportedly far exceeded that of the U.S.2)The number is based on the number of data centers in China, which is the largest in the world. However, there are several assumptions underlying these figures, and it is questionable whether they reflect the impact of China's policy of restricting cross-border data distribution.

Thus, the measurement of cross-border data volume is not consistent, as each agency only produces inconsistent figures with its own assumptions. While combining macro and micro methods, the first step is to search for evidence on cross-border data distribution and the trust that overlaps on top of it. In particular, it is required to present a variety of evidence that data distribution is negatively impacted business when it is impeded.

While studies have been conducted, including estimates of the impact on GDP, focusing on personal data protection regulations, it is necessary to quantitatively analyze the economic impact of data protectionism and data distribution from a higher level and the sense of disincentive from the standpoint of corporate practice in order to consider the impact of data protectionism and data distribution on practice based on the evidence. The results of a preparatory study for this purpose in the ASEAN countries plus India, which was started in 2021, are presented in this report. (Reference A)

Discussion points based on current understanding

First, it is important to bring the Asia-Pacific region closer to a single market through free cross-border data distribution. The greatest advantage of the digital economy lies in its ability to increase efficiency through the aggregation of data and concentration of processing resources, which translates into reduced costs and stable value reproduction. Therefore, the argument for increasing the size of the "digital economic zone" is basically supported by minimizing the restrictions, differences in the regulatory environment, and tariffs imposed due to the cross-border nature of the region.

At the same time, we must consider what regulations are problematic. In order to link this to concrete issues, it is effective to start by sketching the current situation based on as many objective facts as possible about the impediments to digital protectionism and DFFT, and to promote Japan's position at the OECD and APEC in cooperation with the public and private sectors.

DFFT's exit from a single market in the Asia-Pacific region through free cross-border data distribution

The EU's attempt to maintain its own economic zone through the digital single market has stimulated competition for market development among regions, even in the new type of corona coexistence economy. The global market should be based on common principles, but at the same time, it should maintain diversity and aim for higher development through friendly competition. On the basis of Japan's existing economic scale, it is necessary to advocate a unique, trust-based digital economy model, centered on the Asia-Pacific region, without being overly dependent on either the U.S., China, or Europe.

ECIPE (European Institute for International Political Economy) 2014 survey3)have reported that the negative impact of data localization regulations on a country's economy can be up to 1% of GDP. A more extensive and detailed analysis should consider what impact the use of data could have on each country's economy.

In the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), the contents of the agreement on liberalization of data distribution are stipulated in the telecommunications chapter of Chapter 13 and the electronic commerce chapter of Chapter 14, and the member countries have already taken the first step toward a single market in the region. The RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership for East Asia) also includes provisions on e-commerce in Chapter 12.

In addition, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) signed by Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore in 2021 took only eight months to reach agreement, which is exceptionally fast compared to other agreements such as the TPP (more than 10 years). All of these developments reflect the importance of free cross-border data distribution, which aims to create a reliable and unifying digital economy market. A single market is expected to offer many advantages, such as efficiency, scalability, and leveling of supply and demand fluctuations.

Designing "trust" to compensate for the imperfections of data as a resource

Trust is the function that transforms data into value. Trust ensures the stable distribution of large volumes of data, as well as its quality of timely and rapid synchronization and diversity. the concept of the "digital economy" was launched in earnest at the 2016 OECD Digital Ministerial Meeting (Cancun, Mexico), and six years later, in 2022, the The time has come to consider the "next phase" of the digital economy, with a more radical message of purpose.

Cybersecurity, for example, requires increased cooperation in day-to-day countermeasures against technological threats. At the same time, the relative importance of non-technical aspects is increasing, and it is necessary to design and realize a resilient society and organizational culture against attempts to inflict damage and unjustly deprive property through a combination of psychological and social means, such as ransomware. In this context, for example, a mechanism such as insurance could be used to mitigate risks based on market principles, thereby fostering trust in the active use of data.

Role of government and public-private partnerships regarding "trust

Just as many social issues require the involvement of multiple stakeholders (groups with diverse roles), the division of roles is also key in the process of data distribution based on "trust" that will lead to the circulation of the new digital economy. Among these, the role of government can have various ideas and balance points regarding its appropriate level of involvement.

U.S. research firm Edelman's report for 2022.4)Among the four actors (government, media, business, and NGOs), trust in government and media decreased from last year, while trust in business actors was the largest. Lack of decisive policies to control infectious diseases and questions about appropriate reporting in the midst of turmoil may be the main reasons.

Without the cooperation of society as a whole, it will be difficult to foster trust in the digital world. What is required, then, is appropriate policy design and public-private partnerships within the government.

[Note]

1) The World Beyond the Corona, edited by the Center for the Promotion of International Economic Partnership (Sankei Shimbun Publications, 2020)

(2) China's data sphere, twice as large as the U.S., is offensive and defensive, deepening the division A Century of Data: The Cracking Net (Top), Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 2020-11-24.

3) The Costs of Data Localisation: A Friendly Fire on Economic Recovery, ECIPE https://ecipe.org/publications/dataloc/publications/dataloc/

4) 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, Edelman https://www.edelman.com/ trust/2022-trust-barometer

Reference Material A] Summary of the CFIEC Cross-border Data Distribution Study 2021 Report

In the new Corona Disaster, CFIEC has been working to report on trends in cross-border data distribution around the world, both in terms of changes that are accelerating the flow of digital transformation to date and completely new and unexpected changes. In this report, we outline the results of a survey covering eight countries, including India, which was added to the ASEAN countries from January 2021.

■Survey Overview

Countries surveyed: India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Taiwan (8 countries)

Survey period: January 2021 - present

Survey method: (1) Survey forms were distributed to companies in each country via national associations affiliated with the Asia-Pacific IT Industry Association (ASOCIO).

(2) Deployment of survey sheets to companies in each country via MX (MarketXcel)

Number of cases collected: Survey method 1→98 cases (including 80 cases in Vietnam) Survey method 2→400 cases (20 cases x 8 countries)

■Survey Form

Number of questions: up to 18

Questions: Attributes of respondents, status of cross-border data transfers, awareness of regulations on cross-border data transfers, etc.

1 What is the status of data transfer in the world?

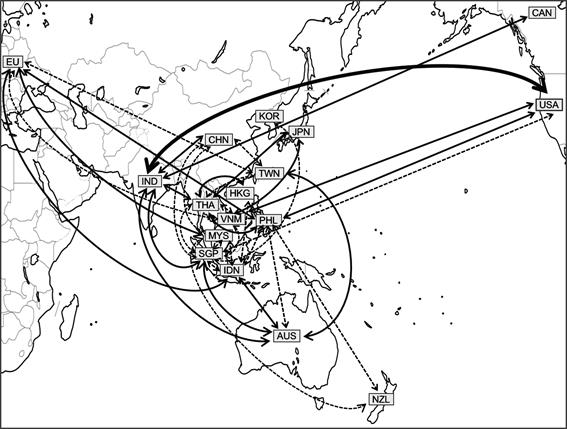

Figure 1 shows the status of data transfers, focusing on ASEAN and neighboring Asian regions. (Data transfers from Japan are not included in this study.) The type of line indicates the amount of data transfers (measured by awareness obtained from the questionnaire, self reported value) as a sense of the relationship between the two regions (thick line > solid line > dotted line).

Figure 1: Global Data Transfer Status Based on Survey Results

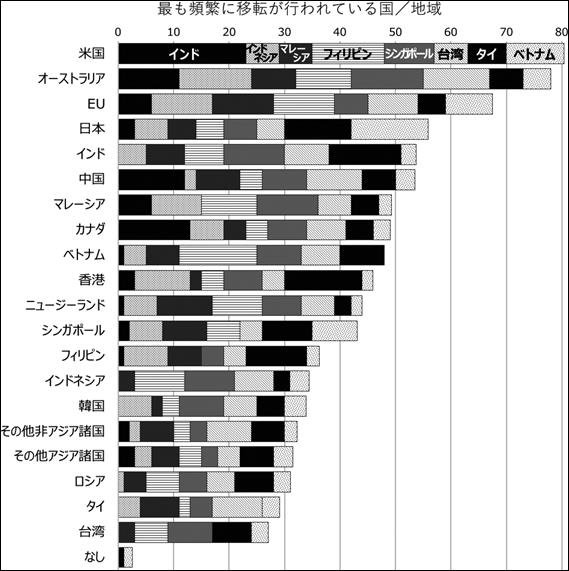

The amount of data transferred was quantified and normalized to enable comparison of relative data flows, and the result showed that transfers between the U.S. and India were the largest. Figure 2 shows that the top destination countries for transfers are outside the ASEAN region (e.g., Japan, the U.S., Europe, Australia, and China). There are also active transfers to intra-regional countries, and there is no country in the region that is prominently positioned as a destination for transfers.

In other words, there is no bias toward any one country or region in terms of data transfer partners. Although data distribution with the U.S. is the most common, there is an awareness that data distribution with other countries and neighboring countries is also very active.

Regarding the volume of cross-border data distribution involving China, some statistics have just reported that it has surpassed the volume of U.S. cross-border data distribution. At least in terms of business awareness, China is second only to the U.S., Australia, the EU, Japan, and India. However, it is conceivable that its presence may increase depending on the future situation.

Figure 2: Data transfers as a realization of the ASEAN India region (in order of major transfers and source of transfers)

2 The contents of cross-border data are diverse in both direction and type of distribution.

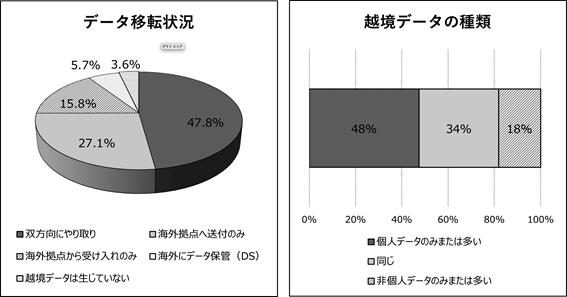

In terms of awareness of data transfer destinations, as shown in Figure 2, there is little bias toward a narrow range, indicating that data distribution itself is a multi-directional and diverse reality. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Direction of Data Transfer and Percentage of Personal Data

Looking at the type of cross-border data, transfers that are determined to be personal data predominate, but the total number of responses that are equal or only non-personal data is the majority. This indicates a high level of interest in the regulation of personal data, and also indicates that a certain number of companies in some industries sensibly believe that transborder transfers of non-personal data are the main type of transborder transfers. (Figure 3)

3 Interest in data distribution regulations in the ASEAN India region

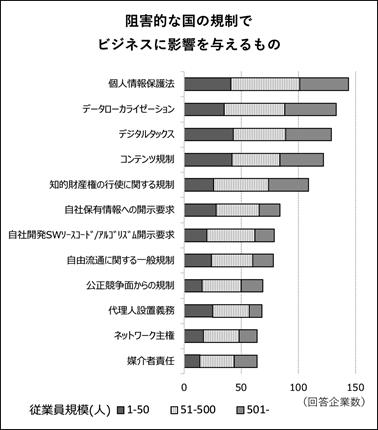

When asked about the impact on business of government regulations that have a disincentive effect on business, the largest number of companies consciously consider regulations related to the protection of personal information to be important. There is no marked difference in trend by the size of the number of employees, and this can be seen as a common concern regardless of the size of the company.

Following privacy protection, data localization (regulation of data and related equipment installed and maintained in-country), digital taxation, content regulation, and intellectual property regulation were reported as regulations of high interest regardless of the size of the company. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Disincentives for Transborder Data Regulation

Although government disclosure requirements for information held by the company and source code disclosure requirements (government access) are relatively new concerns that are just beginning to be discussed, it is apparent that there is already a certain amount of interest in this area.

It can also be said that small and medium-sized enterprises are equally aware of the need to consider the protection of personal information in cross-border data, without relying heavily on the size of the company in terms of the number of employees.

Another analysis shows that Australia, which is generally considered to have a strict privacy law system, is a target country for active data transfer in Figure 2, but also has strict regulatory restrictions in terms of awareness surveys.

The fact that the requirement for domestic installation of server facilities and other data-related equipment (data localization) is the second top concern after personal information protection regulations suggests that there is a growing trend toward expanding one's business overseas. At the same time, there is a growing awareness of the need to seek business advantages from the accumulation of data beyond geographical constraints, which is the essence of data, and it is likely that many respondents saw this as a regulatory factor that would hinder this trend.

Government access (access by government agencies to data held by the private sector) is one of the reasons for the Schrems II decision, in which the Court of Justice invalidated the "Privacy Shield," which was the framework for cross-border personal data transfers between the US and EU. In Japan and elsewhere in the region, the possibility that one's data transferred to a foreign country could be unwittingly referenced and used by the government in accordance with the legal system and government policies of the destination country is considered to be a potential source of anxiety for consumers. In addition, from the standpoint of companies entrusted with personal data, the potential risk of undermining consumer rights outside the scope of their own responsibility is undesirable for business development.

Respondents who indicated that cross-border data transfer regulations have an impact on their business and who are more concerned about data distribution were also more likely than those who are not to believe that government access will have a significant impact. Although awareness is still low, there is a high level of awareness of concerns about potential impacts.